What Was The 2009 U.s. Preventive Services Task Force Proposal Regarding Routine Mammograms?

Abstract

At that place are few medical problems that take generated as much controversy as screening for chest cancer. In science, controversy often stimulates innovation; nevertheless, the intensely divisive contend over mammographic screening has had the opposite event and has stifled progress. The same two questions—whether it is better to screen annually or bi-annually, and whether women are best served past beginning screening at 40 or some afterward historic period—have been debated for xx years, based on data generated 3 to four decades ago. The controversy has continued largely because our electric current approach to screening assumes all women have the same chance for the same type of breast cancer. In fact, nosotros now know that cancers vary tremendously in terms of timing of onset, rate of growth, and probability of metastasis. In an era of personalized medicine, we have the opportunity to investigate tailored screening based on a woman's specific risk for a specific tumor type, generating new data that tin inform best practices rather than to continue the rancorous fence. It is time to motion from fence to wisdom past asking new questions and generating new knowledge. The WISDOM Written report (Women Informed to Screen Depending On Measures of hazard) is a pragmatic, adaptive, randomized clinical trial comparison a comprehensive gamble-based, or personalized approach to traditional annual breast cancer screening. The multicenter trial volition enroll 100,000 women, powered for a main endpoint of non-inferiority with respect to the number of late stage cancers detected. The trial will make up one's mind whether screening based on personalized risk is every bit safe, less morbid, preferred by women, will facilitate prevention for those most likely to do good, and adapt equally we learn who is at risk for what kind of cancer. Funded by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Found, WISDOM is the production of a multi-year stakeholder engagement procedure that has brought together consumers, advocates, primary intendance physicians, specialists, policy makers, technology companies and payers to help break the deadlock in this debate and accelerate towards a new, dynamic arroyo to breast cancer screening.

Introduction

Annual screening mammography—the almost common arroyo in the Usa today—has its roots in the big, randomized screening trials of the 1980s.ane The first trial of annual screening, the U.S. Health Insurance Plan of Greater New York, began in 1963 and included 31,000 women in each arm.two At 18 years of follow-upwards, information technology showed a 25% reduction in mortality, although do good to women in their forties accrued after they were 50. The overview of the Swedish trials of bi- or triennial screening showed a relative reduction in chest cancer bloodshed of 21%, with maximum benefit for women in their sixties.3 The degree and timing of benefit to younger women in particular has generated a great deal of controversy.4 Even a decade later, there remains a continuing debate over the methodologic flaws of each of these studies, the cyberspace upshot of which has impeded consensus on public recommendations for chest screening.five,6,seven

From the kickoff, translating these studies into population-based screening recommendations stirred controversy, with contend focused on the frequency and most appropriate age to begin screening. The January 1997 Consensus Development Panel convened past the National Institutes of Wellness recommended women aged 40–49 be informed of the benefits and risks of screening and decide for themselves.8 The National Cancer Institute (NCI) and American Cancer Society (ACS), notwithstanding, recommended regular screening for women in their forties while disagreeing on screening frequency, with the former recommending every i–2 years, the latter annually. Partly because of the controversy generated, the NCI subsequently stopped issuing screening guidelines.

At present, 20 years later, nosotros observe ourselves in a familiar place—still reviewing and reanalyzing data from the same trials, debating the optimum age to begin and interval, with professional societies that set up guidelines compelled to "have a side" in the debate. The controversy post-obit the 2009 JAMA commentary "Rethinking Screening"9 and updates to USPSTF guidelines10 illustrates how entrenched both sides have become. Consensus on recommendations remains afar.

The US Preventative Job Force systematic review ended in 2015,xi much like information technology had in 2009,10 that mammographic screening benefits women over 50 and that biennial, non almanac, screening was recommended for women ages 50–74. After weighing the balance of harms and benefits for women aged 40–49, screening was not recommended routinely for women in their forties. Instead, the USPSTF suggested an individualized approach taking patient risk and personal preference into business relationship. In contrast, 2017 guidelines from the American College of Radiology and the Club of Chest Imaging currently recommend almanac screening starting at age 40.12 The American Cancer Social club has revised their guidelines and recommend annual mammograms for women over 45 of average risk, with women betwixt the ages of 40–44 provided the opportunity to begin almanac screening. Women over the age of 55 are recommended to receive biennial screening, although annual screening may be considered.thirteen

Although the academic debate has progressed little in these 30 years, what has changed is public awareness of this upshot. The vast press coverage of the Canadian National Breast Cancer Screening Report (CNBCSS) in 2014 brought the potential harms of screening into the public spotlight. Non only did the 25-year analysis of the CNBCSS evidence, as information technology had at both ten and 15 years, that annual screening failed to reduce breast cancer bloodshed, information technology provided the first-always estimates of overdiagnosis in a population-based annual screening program: half of all screen-detected not-palpable cancers were estimated to exist indolent lesions that would otherwise never accept come to clinical attention.14

For some, this result simply confirmed previous findings showing that up to 20% of all cancers (50% of screen-detected cancers) fall into the category of overdiagnosis15,xvi,17—meaning a adult female has a greater chance of beingness over-diagnosed than of having her life saved by screening.18 Others pointed to studies demonstrating at that place is little, if any overdiagnosis in breast cancer,nineteen, 20 labeling CNBCSS as a flawed assay or simply the latest way to attack screening. The debate reached such an unhealthy tenor that published exchanges fifty-fifty included accusations of a scientific conspiracy to reduce access to mammography.21, 22

Similar the screening debates that preceded it, the controversy surrounding overdiagnosis has now settled into a familiar pattern. Information technology focuses on largely technical arguments over statistical assumptions, corrections for atomic number 82 fourth dimension bias and varied demographics23, 24 that create uncertainties in the data and ultimately have shifted the contend into the realm of opinion, rather than fact. Recent characterization of a molecular profile to define an ultralow adventure biology may provide a tool to more considerately categorize ultralow take a chance breast cancers that have little systemic risk of progression. This is an of import advance that may aid us to improve our ability to treat the affliction and further tailor individual screening recommendations.25

We must remember, however, that the data nosotros are arguing over are from decades-quondam trials, from an era before most of the effective systemic therapies were bachelor. That at that place is an impact of modern systemic therapies on reducing breast cancer mortality is undeniable—some gauge that systemic therapy accounts for 2/3 of the observed reduction in mortality.26, 27 The rise of endocrine therapy28, 29 may as well mitigate the impact of finding some cancers after.

Whether one believes these figures or not, the takeaway is that we are stuck in an countless bicycle of academic argue, arguing over data that take little context in the modern treatment setting. Breast cancer treatment continues to rapidly evolve towards a patient-centered, precision medicine approach that recognizes what is perchance the most important lesson we have learned over the past two decades of research: that breast cancer is not a monolithic entity, but a spectrum of disease. From indolent lesions of epithelial origin (IDLE)ix requiring no handling, to ambitious disease requiring equally aggressive treatment, it has resisted all our attempts to lump information technology into a unmarried bin.

Yet nosotros continue our one-size-fits-all approach to breast cancer screening. Information technology is contrary to the very nature of the disease. Nosotros cannot continue to focus the entirety of our efforts on a screening approach that is based on an outdated agreement of breast cancer biology, expecting that the uncertainties and debate will finally be resolved. Instead, nosotros must be willing to innovate and to entertain new paradigms of screening that incorporate our electric current understanding of breast cancer, its handling and risk susceptibility by putting them to the test.

Nosotros may accept little pick. Because the consequences of failing to do and so may exist to farther alienate the very women screening is supposed to help.

What women want: ameliorate, not more than screening

Even though generations of women educated in the benefits of screening mammography generally regard information technology positively, feel shows it is a fragile trust. A single false positive can cause psychological distress for upwards to three years and reduce adherence to subsequent screening by 37%.xxx,31,32,33,34

Considering the specificity of mammography is more often than not accustomed to be ~ 90% (e.thou., ane in x are false positive), whereas the real breast cancer charge per unit is ~ 5 in one thousand women, the majority of abnormal mammograms are, in fact, false positives. Later x years of annual screening, over half of all women receive a false-positive recall and vii–nine% have a fake-positive biopsy.35

Furthermore, in the wake of the CNBCSS, data concerning overdiagnosis is increasingly available to women,36 undermining their confidence in screening. Women given controlled, qualitative, and quantitative education on the risks of overdiagnosis have less positive attitudes about screening and demonstrate reduced intent to screen.37 Similarly, main care physicians, key influencers in a woman's screening decisions, are far less willing to refer patients 40–49 for screening when fully educated about the potential risks/benefits of screening.38

Further, our conflicting recommendations have made this divisive debate a public 1, sowing distrust and a deepening confusion for women over how to foreclose the disease that scares them the most.39, 40

The question nosotros need to be asking, therefore, is not whether we should screen more or less, earlier or afterwards. It is how tin we make screening better for women, reduce false-positive recalls and improve our power to more than accurately forbid and find clinically significant cancers sufficiently early on. This is, later all, is what women tell us they want41 and what we accept observed to appointment in the WISDOM trial (described below).

The answer is simply that nosotros must move on. We must begin developing and testing new and ameliorate approaches that answer to women's needs. Fortunately, in this respect, there is ane thing upon which nosotros all agree—women must have the opportunity to make informed screening choices.

Individualized, informed choice

Overwhelmingly, women want data about their personal risk of breast cancer.42, 43 Currently, only 10% have authentic perceptions of their personal take a chance and 40% accept never discussed their personal breast cancer risk with a doctor.44 Yet, a realistic view of their take chances is prerequisite to making informed screening decisions.

We have the tools to better inform women of their personal chance, through well characterized models that contain family history and breast density, endocrine exposures, cistron mutations, and atypia,45,46,47,48,49 along with a number of common gene variants.fifty, 51 They teach us that not all women whom we allocate for screening purposes as "average-risk," actually have the same lifetime take chances of breast cancer. Armed with a better understanding of their private hazard, such women will expect—and demand—screening recommendations commensurate with their personal gamble.

Unless nosotros are prepared to ignore the mod tools available to us, we are therefore compelled to shepherd breast cancer screening into the era of precision medicine. Now is the time to begin evaluating a patient-centric model, focusing on individually tailored recommendations on when to start, when to end, and how often to screen, depending upon a woman's personal risk. Just through clinical testing tin can we constitute the testify that tells the states how best to apply risk.

The idea of risk-based screening is not revolutionary. In fact, we already do it, although in a crude fashion. Information technology is standard of practice for loftier risk women with mutations in the BRCA genes and first degree relatives from high risk families to brainstorm screening at a much earlier age, and to practise then more frequently (annual mammogram alternate with annual MRI).52 But our understanding of breast cancer risk goes much further than our electric current screening recommendations reflect. Our failure to incorporate our current understanding of personal take a chance into our screening recommendations ways we may be asking some women to accept run a risk/benefit ratios they might not exist comfortable with if they were fully informed.

Within the context of well-designed, randomized, controlled clinical trials, we have the ability to investigate new screening models in a safety, systematic manner, outset with conservative estimates that minimize the chances of misclassification of risk and avoid underscreening. If nosotros are successful, it could assistance establish a new baseline for cancer screening, reduce defoliation and anxiety for women over conflicting recommendations, meliorate women's perception of their true take a chance of breast cancer, meliorate adherence,53 and reinforce conviction in providers. Perhaps virtually importantly, information technology allows u.s. to learn who is at hazard for what kind of cancer, and constitute a wheel of continuous improvement in breast cancer screening.

Risk-based screening may or may not be the answer to all of screening's shortcomings, but it is perhaps an answer to the current deadlock in which we observe ourselves. In the words of philosopher David Hume, it is time "we start spilling our sweat, and non our blood."

The WISDOM study: overcoming challenges

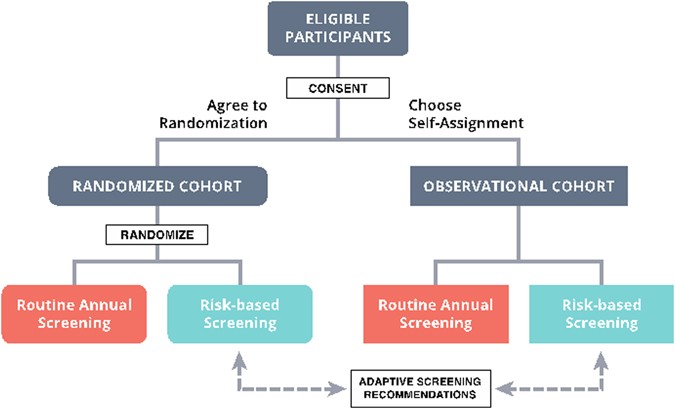

Nosotros have recently been awarded a grant from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) to evaluate a risk-based screening arroyo within a pragmatic, controlled trial. The "WIDSOM" study (Women Informed to Screen Depending On Measures of chance) is a multicenter trial comparing risk-based screening to almanac screening in 100,000 women aged 40–74, initially opening in the Athena Chest Wellness Network in California and the Midwest (Table 1). The study is a "preference tolerant design" (Fig. one) that encourages women to be randomized (n~ 65,000) but also allows self-assignment for those with strong personal preference for either annual or risk-based screening (a pilot study was conducted in 2015 in which 74% of women agreed to randomization). Importantly, WISDOM is an adaptive design, assuasive u.s. to larn and adjust, continuing to meliorate the hazard-assessment and screening recommendation models over the grade of the trial.

Overall WISDOM study schema

An essential aspect of developing WISDOM has been the engagement of all stakeholders, including consumers, policy makers/guideline organizations and multiple specialties, and payers, to agree upfront on metrics for success. This ensures the trial remains relevant to the needs of the end-user and sets the stage for rapid adoption should it bear witness successful.

Patients and advocates in detail, through the Athena Consumer and Customs Advisory Commission, have been key partners in WISDOM since its conception. The preference-tolerant design that allows all women to participate regardless if they have potent personal reservations about beingness randomized grew from vigorous discussions with this grouping. The consumer vocalism is deeply embedded in WISDOM, with influence in all aspects of written report design and planning, including enrollment strategies, consent processes, primary care md outreach and education, risk notification, and participant retentiveness.

The buy-in of health care payers is essential to enable rapid dissemination once results are presented. Modeling shows a risk-based strategy will be more cost constructive in terms of screening, but requires an initial outlay of resources for former genetic testing and comprehensive risk assessments. Later on nigh two years of discussion and negotiation, WISDOM's "Payer Working Group", led by Blue Shield of California and including all insurers in California, has reached an agreement to implement a "Coverage with Show Development" model to embrace clinical costs not funded through PCORI.54 This model allows innovative treatment approaches to be tested transparently. The utilise of a coverage model that fosters the development of evidence, using a coverage with trial participation approach, allows understanding on metrics for adoption and should shorten the timeline for adoption. By engaging payers early, should the study show successful, we will have laid the foundations to address future challenges in implementation related to standard coverage. Nosotros are in the procedure of engaging other payers.

The well-nigh formidable challenge in terms of stakeholders in developing a trial of risk-based screening, given the voracity of the bookish debate, lies inside the academic community. Among the highest priorities has been to define acceptable parameters of risk assessment, stratification and screening recommendations. Nosotros take as well invested considerable effort to achieve consensus regarding what constitutes success. WISDOM's 'Run a risk Thresholds Group' and 'Chief Care Physician Working Group," consisting of primary intendance teams, representatives of the radiology customs and others have shared these tasks.

Risk assessments and recommendations

The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) model was selected as the foundation of individual risk assessments for WISDOM, based on its accuracy, ease of implementation, its large (>1 million women) multiethnic target population, and incorporation of ethnicity and breast density every bit risk factors.55, 56 Additional assessments also include polygenic risk based on well-nigh 200 SNPs, as well equally a 9 high-penetrance cistron mutation panel.

In translating individual risk to screening recommendations, the primary consideration of the working groups was to develop guidelines that were sufficiently conservative to minimize risk of potential harm from underscreening, nevertheless progressive enough to minimize potential harm from overdiagnosis, while permitting upshot measures with sufficient study ability. The consensus run a risk stratification and related screening recommendations to be employed within WISDOM are shown in Table 2, and include more than frequent screening for those at highest risk or those at risk for faster growing (e.k., hormone negative) cancer. In the risk-based assessment arm, no woman will receive a recommendation for less screening than electric current USPSTF guidelines—individual take a chance ≥ i.three% over 5 years initiates screening. Considering the uptake of risk-reducing interventions has been very poor despite level 1 prove of benefit, we will use a stringent threshold (top 2.v percentile of risk for breast cancer by historic period group, or lifetime hazard in the range of 30% or college) for identifying participants to target and counsel virtually endocrine risk-reducing therapy. The gene-based tests also inform the risk for hormone positive or negative chest cancer and impact screening and prevention recommendations. Boosted details on the rationale and prove used to develop this model are published elsewhere.57, 58

A shared controlling (e-prognosis) tool based on recent modeling of comorbidity and impact of screening59 volition be used to identify women unlikely to benefit from screening due to limited life expectancy. These rules will inform our adventure assignments, age to start, age to stop, frequency, and advisable modality of screening. The trial is designed to adapt over time, and refine categorization and screening frequency based on the actual cancer charge per unit and biology of tumors that develop.

Defining success

If, after completing WISDOM, we are to avoid simply calculation additional fuel to the fire of the screening argue, the scientific questions nosotros ask must be well defined and the answers definitive. This is specially challenging given the nature of the current contend and is farther complicated by statistical requirements, population size limitations and the five-yr follow-up limitation of the funding. Such deliberations within WISDOM working groups strengthened the study significantly, emphasized safety equally the overriding priority and established a series of outcomes with achievable and highly relevant goals.

WISDOM's primary endpoints are, starting time, to make up one's mind whether risk-based screening is non-inferior to annual screening for late-stage cancers detected. The outcome is the number of Stage IIB or higher cancers found using personalized vs. annual screening. The study has been powered assuming annual incidence rates of 95 Stage IIB or higher cancers per 100,000 women in each arm.60 Over 65,000 randomized patients, this provides 90% power to find a divergence lower than 0.05% in risk of being diagnosed with Phase IIB or higher in the personalized vs. annual arm in a given twelvemonth (83% for a deviation <0.035%).58

Second, we will compare the morbidity of personalized vs. almanac screening on the basis of the number of biopsies performed. Bold 16% of first time mammograms and viii% of subsequent screens pb to false positive recalls,61 65,000 patients equally randomized betwixt annual and personalized screening offers 90% power to detect a difference as small as 1.1% (22 vs. 20.ix%).

Additional secondary objectives will further our understanding of the impacts of personalized screening and include measures of morbidity (e.g., rates of systemic therapy, rates of DCIS, chemoprevention) and the comparative attitudes and acceptance of each screening modality by women enrolled in the trial (e.chiliad., adherence, measures of anxiety, decision regret). Finally, we will determine whether an agreement of personalized risk, specially the ability to predict hormone positive chest cancer, will provide better motivation for and uptake of endocrine risk reducing therapies and lifestyle changes.

Since opening in September 2016, Over 4000 women have enrolled in WISDOM. About two-thirds accept agreed to randomization. The other ane-third opted to self-select their screening approach in the observation arm: 85% have elected for personalized screening. Although preliminary, our experience to engagement provides critical insight into the comfort women feel with the concept of individualized, adventure-based screening.

Conclusions

The U.s. is the only state where annual screening starting at historic period forty is standard do, yet our breast cancer mortality rate is no amend than countries that screen less.62 Clearly, there is room for comeback. Progress will only come up past investigating other possibilities. The WISDOM study will evaluate one such possibility—screening based on a woman's private gamble—opening its starting time site in August 2016, expanding to other sites nationally in 2017. It is certainly unlikely that all women benefit every bit from screening. Investing in businesslike studies like WISDOM allows us to learn who is at risk for what kind of breast cancer, tailor screening accordingly and build a new framework for continuous improvement.

References

-

Nyström, L. et al. Breast cancer screening with mammography: overview of Swedish randomised trials. Lancet 341, 973–978 (1993).

-

Shapiro, South. Periodic screening for chest cancer: the HIP Randomized Controlled Trial. Health Insurance Program. JNCI Monogr. 1997, 27–30 (1997).

-

Nyström, Fifty. et al. Long-term effects of mammography screening: updated overview of the Swedish randomised trials. Lancet 359, 909–919 (2002).

-

Tabár, Fifty., Duffy, S. West. & Chen, H. H. Re: Quantitative interpretation of historic period-specific bloodshed reductions from the Swedish breast cancer-screening trials. JNCI J. 88, 52–55 (1996).

-

Nelson, H. D. et al. Harms of chest cancer screening: systematic review to update the 2009 U.South. preventive services job force recommendation. Ann. Intern. Med. 164, 256 (2016).

-

Gøtzsche, P. C. & Jørgensen, Thousand. J. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 156, 193 (1996).

-

Shieh, Y. et al. Population-based screening for cancer: hope and hype. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 13, 550–565 (2016).

-

National Institutes of Wellness Consensus Development Conference Statement. Breast cancer screening for women ages 40–49. Natl. Inst. Wellness Consens. Dev. Console 89, 1015–1026 (1997).

-

Esserman, L., Shieh, Y. & Thompson, I. Rethinking screening for chest cancer and prostate cancer. JAMA 302, 1685–1692 (2009).

-

Nelson, H. D. et al. Screening for chest cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 151, 727–37 (2009).

-

Siu, A. L. On behalf of the U.S. Preventive services task forcefulness. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 164, 279 (2016).

-

Mainiero, Chiliad. B. et al. ACR appropriateness criteria breast cancer screening. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 13, R45–R49 (2016).

-

Oeffinger, Grand. C. et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average hazard: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA 314, 1599–1614 (2015).

-

Miller, A. B. et al. 20 five year follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian National Chest Screening Study: randomised screening trial. BMJ 348, g366 (2014).

-

Esserman, 50. J. et al. Affect of mammographic screening on the detection of adept and poor prognosis breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 130, 725–734 (2011).

-

Welch, H. Thou. & Black, Due west. C. Overdiagnosis in cancer. JNCI J. 102, 605–613 (2010).

-

Marmot, M. Thou. et al. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Br. J. Cancer 108, 2205–2240 (2013).

-

Pace, Fifty. Eastward. & Keating, N. Fifty. A systematic assessment of benefits and risks to guide chest cancer screening decisions. JAMA 311, 1327–1335 (2014).

-

Duffy, South. W. et al. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of chest cancer: estimates of overdiagnosis from two trials of mammographic screening for breast cancer. Chest Cancer Res. 7, 258–265 (2005).

-

Paci, Due east. & Duffy, S. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of breast cancer: overdiagnosis and overtreatment in service screening. Breast Cancer Res. 7, 266 (2005).

-

Kopans, D. B. Arguments against mammography screening continue to be based on faulty science. Oncologist 19, 107–112 (2014).

-

Bleyer, A. Were our estimates of overdiagnosis with mammography screening * in the united states "based on faulty scientific discipline"? Oncologist 19, 113–126 (2014).

-

Kaniklidis, C. Beyond the mammography debate: a moderate perspective. Curr. Oncol. 22, 220 (2015).

-

Yaffe, M. J. Response to: 'Beyond the mammography debate: a moderate perspective'. Curr. Oncol. 22, e401–3 (2015).

-

Esserman, Fifty. J., Yau, C., Thompson, C. K., van t Veer, 50. J., Borowsky, A. D., Hoadley, K. A., et al. Utilize of Molecular Tools to Place Patients With Indolent Breast Cancers With Ultralow Risk Over 2 Decades. JAMA Oncology. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1261 (2017).

-

Early on Chest Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 365, 1687–1717 (2005).

-

Berry, D. A. et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1784–1792 (2005).

-

Kalager, M., Zelen, M., Langmark, F. & Adami, H.-O. Effect of Screening mammography on breast-cancer mortality in Norway. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 1203–1210 (2010).

-

Dowsett, 1000. et al. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 509–518 (2010).

-

Bond, M. et al. Systematic review of the psychological consequences of faux-positive screening mammograms. Wellness Technol. Assess. 17, 1–170 (2013).

-

Klompenhouwer, E. Yard. et al. Re-omnipresence at biennial screening mammography following a repeated false positive call up. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 145, 429–437 (2014).

-

McCann, J., Stockton, D. & Godward, South. Bear upon of false-positive mammography on subsequent screening attendance and chance of cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 4, 954 (2002).

-

DeFrank, J. T. et al. Influence of false-positive mammography results on subsequent screening: practise medico recommendations buffer negative effects? J. Med. Screen. nineteen, 35–41 (2012).

-

Dabbous, F. M. et al. Touch of a false-positive screening mammogram on subsequent screening behavior and stage at breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 26, 397–403 (2017).

-

Elmore, J. G. et al. Ten-year take chances of false positive screening mammograms and clinical chest examinations. N. Engl. J. Med. 338, 1089–1096 (1998).

-

Ghanouni, A. et al. Data on 'overdiagnosis' in breast cancer screening on prominent u.k.- and Australia-oriented health websites. PLoS ONE 11, e0152279 (2016).

-

Hersch, J. et al. Apply of a decision aid including information on overdetection to support informed choice about breast cancer screening: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 385, 1642–1652 (2015).

-

Bryan, T., Castiglioni, A., Estrada, C. & Snyder, E. Touch on of an educational intervention on provider knowledge, attitudes, and comfort level regarding counseling women ages forty–49 about breast cancer screening. JMDH eight, 209–216 (2015).

-

USPSTF. Breast Cancer Screening Recommendations Could Endanger Women. http://www.acr.org/About-Us/Media-Center/Press-Releases/2016-Press-Releases/20160111-USPSTF-Breast-Cancer-Screening-Recommendations-Could-Endanger-Women. Accessed 10 May 2016 (2016).

-

Squiers, L. B. et al. The Public's Response to the U.Due south. Preventive services job force's 2009 recommendations on mammography screening. Am. J. Prev. Med. xl, 497–504 (2011).

-

The Society for Women'southward Health Research. What Women Desire: Expectations and Experiences in Breast Cancer Screening. http://swhr.org/science/swhr-mammography-survey/. Accessed 10 May 2016 (2014).

-

Fisher, B. A., Wilkinson, L. & Valencia, A. Women's interest in a personal breast cancer hazard assessment and lifestyle advice at NHS mammography screening. J. Public. Health. 39, 1–9 (2016).

-

Sphingotec, L. 50. C. Survey: Majority of Women Do Not Talk over Breast Cancer Risks or Mammography Screening Limitations with Healthcare Providers. http://www.marketwired.com/press-release/survey-majority-women-practise-not-discuss-breast-cancer-risks-mammography-screening-limitations-2016448.htm. Accessed fifteen June 2016 (2015).

-

Printz, C. Almost women have an inaccurate perception of their breast cancer take chances. Cancer 120, 314–315 (2014).

-

Costantino, J. P. et al. Validation studies for models projecting the risk of invasive and total breast cancer incidence. JNCI J. 91, 1541–1548 (1999).

-

Parmigiani, G., Berry, D. & Aguilar, O. Determining carrier probabilities for breast cancer-susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 62, 145–158 (1998).

-

Tyrer, J., Duffy, S. W. & Cuzick, J. A chest cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat. Med. 23, 1111–1130 (2004).

-

Claus, E. B. Adventure models used to counsel women for breast and ovarian cancer: a guide for clinicians. Fam. Cancer 1, 197–206 (2001).

-

Ozanne, E. K., Howe, R., Omer, Z. & Esserman, Fifty. J. Evolution of a personalized decision aid for breast cancer adventure reduction and management. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 14, 4 (2014).

-

Darabi, H. et al. Chest cancer risk prediction and individualised screening based on common genetic variation and breast density measurement. Breast Cancer Res. 14, R25 (2012).

-

Mavaddat, N. et al. Prediction of breast cancer risk based on profiling with common genetic variants. JNCI 107, djv036–djv036 (2015).

-

Daly, M. B. et al. Genetic/Familial Loftier-Take a chance Assessment: Breast and Ovarian, Version i.2017. NCCN Clinical Exercise Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN, 2016).

-

Edwards, A., Unigwe, Southward., Elwyn, G. & Hood, K. Effects of communicating private risks in screening programmes: cochrane systematic review. BMJ 327, 703–709 (2003).

-

Rosenberg-Wohl, South., Thygeson, M., Fiscalini, A. South. et al. Private payer participation in coverage with bear witness development: a case written report. Health Affairs, March 14 (2017).

-

Tice, J. A. et al. Using clinical factors and mammographic chest density to judge breast cancer run a risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann. Intern. Med. 148, 337–347 (2008).

-

Vachon, C. Thousand. et al. The contributions of breast density and common genetic variation to breast cancer risk. JNCI J. 107, 397–400 (2015).

-

Shieh, Y., Eklund, M., Madlensky, L., Sawyer, S. D., Thompson, C. K., Stover Fiscalini, A., et al. Breast Cancer Screening in the Precision Medicine Era: Risk-Based Screening in a Population-Based Trial. JNCI J. 109, djw290 (2017).

-

Eklund, M., Broglio, C., Yau, C., Conner, J., Esserman, L. The WISDOM Chest Cancer Personalized Screening Trial: Design past System Analysis (submitted to JNCI).

-

Lee, S. J., Smith, A. S., Widera, E. Cancer screening. ePrognosis (online). https://eprognosis.ucsf.edu. Accessed 30 March 2017.

-

Esserman, L. J. et al. Biologic markers decide both the risk and the timing of recurrence in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Care for. 129, 607–616 (2011).

-

Kerlikowske, K. et al. Outcomes of screening mammography by frequency, breast density, and postmenopausal hormone therapy. JAMA Intern. Med. 173, 807–816 (2013).

-

Jemal, A., Center, Thou. Grand., DeSantis, C. & Ward, Eastward. Thousand. Global patterns of cancer incidence and bloodshed rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. xix, 1893–1907 (2010).

Author information

Affiliations

Writer notes

-

Members of the Wisdom Study and Athena Investigators are listed earlier references.

Consortia

Contributions

The ideas that are expressed in this commentary are the result of a multiyear collaboration of the Athena Breast Health Network and resulted in the submission of a grant proposal to the Patient Centered Enquiry Outcomes grouping. The kickoff writer summarized the piece of work and the rationale for the proposed WISDOM study in the form of this commentary. All of the wisdom written report and Athena investigators have read the manuscript and provided comments and have certified that the commentary captures the scientific ground underlying and the rationale for opening the WISDOM study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional data

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other 3rd party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If cloth is not included in the commodity's Artistic Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted utilize, y'all will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this commodity

Cite this article

Esserman, L.J., the WISDOM Study and Athena Investigators. The WISDOM Study: breaking the deadlock in the breast cancer screening debate. npj Breast Cancer 3, 34 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-017-0035-5

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41523-017-0035-five

Further reading

What Was The 2009 U.s. Preventive Services Task Force Proposal Regarding Routine Mammograms?,

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41523-017-0035-5

Posted by: bussfirmervis.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Was The 2009 U.s. Preventive Services Task Force Proposal Regarding Routine Mammograms?"

Post a Comment